…and they were really proud of their nurse-daughter.“

Nurse training in a Jewish institution

Thea Levinsohn-Wolf, Stations of a Jewish Nurse. Germany – Egypt – Israel, Frankfurt am Main 1996, page 26

The first Jewish nursing association was founded in the 1890s. They dedicated themselves to the training of nurses and helped establish nursing as a career. This was also confirmed by Nurse Selma Mayer, who was trained in Hamburg and went to Palestine in 1916. She reported that she herself and a colleague were the first Jewish nurses who received a German national diploma: “The first time that Jewish nurses sat for examinations by the German authorities and received a German State Diploma was in 1913”.1

In 1921 one still assumed that for a career in nursing “girls and women from good stock would be preferentially considered” 2. However in practice, the daughters from wealthy families to whom this was addressed were often interested in studying medicine. As nursing offered a good level of social security, it was attractive for girls and young women who were dependent on a regular income. So training became available to the “lower circles” meaning cooks, servant girls, shop women, governesses, Kindergarten teachers and primary school teachers”3. The desired age for entry into training was between 20 and 30 years of age, so that it was required that a certain level of maturity gained through work experience in different fields could be assumed and that willingness to learn was present4.

However, as a result of the First World War. there was a disruption to this development. Gustav Feldmann, a Jewish doctor practising in Stuttgart who campaigned time and time again for the “establishment and nurturing organisation of professional Jewish nursing in Germany,”5 wrote in 1924 that “during the War the influx of pupils in all the associations almost completely ran dry; in the first few post-war years he had actually completely stopped working because all the young girls mostly moved into trade and industry”6. In the impoverishment of the middle classes during the economic crisis of the 1920s he, however, also saw the chance that nursing “in a short time would become fully appealing once again”7. In total, by the end of the 20s, the Jewish associations had trained more than 1,000 nurses, whereby the organisation of training by different associations resulted in “overall a very colourful and inconsistent picture” 8.

Thea Wolf conformed to the description of requirements mentioned above when she joined the Verein für jüdische Krankenpflegerinnen zu Frankfurt am Main (Jewish Nurses Association in Frankfurt on the Main) in 1927 for training. She was 20 years old, had had previous work experience as an accountant and Kindergarten teacher and was looking for a way to earn a living. She was born in 1907 and lived in the middle-class household of her parents, the butcher Moritz Wolf and his wife Jeanette, on the edge of the so-called “working-class neighbourhood” in Essen. In her youth Thea was already a member of the Jewish youth movement and attended to the Jewish emigrants from Poland who came to the Ruhr area after the First World War. Thea Wolf went to commercial college and became an accountant. This part of her life she assessed later in the following way: “My two-year period of employment ended with the company’s declaration of bankruptcy and I was overjoyed,” as she did not want to waste her time on a “lifeless occupation”9

The motivation to become a nurse

One fundamental goal specific to Jewish nursing was to prove that Jewish nurses were just as selfless, sacrificing and as obedient as their Christian colleagues and that the leadership of the Jewish nursing associations was on a par with those of the other motherhouses; this was, for instance, documented in 1928 and 1929 in articles in the monthly booklet of the Jewish Grand Lodge B’nai B’rith10. In order to achieve this goal, they relied predominantly on female nurses and it was argued that the profession “is like no other in corresponding to the natural abilities and disposition of women, conferring so much inner satisfaction and guaranteeing the bearer of the title a generally respected position.”11

From the accounts of the nurses themselves, it becomes clear how important wanting to help was for them. Nurse Selma formulates it this way: “Because I lost my mother very early […] a strong need grew in me to give people that which I had missed so much: mother-love and love of human beings. Therefore I chose the profession of nursing.”12 Also Thea Wolf and her sisters who often wanted to move away from the poor quarters of the city, heard from their mother time again: “Children, if we were to move away from here we would forget the poor and one must not do that.”13 Thea was also used to taking along with her own mid-morning snack some sandwiches for her fellow pupils who were needy; when she received new clothes on a religious or public holiday she passed on an older piece of clothing to the poor in return.

A great desire was fulfilled as Thea Wolf joined the Frankfurt nursing staff and she expressed this as follows: “Everything seemed to me sensible, necessary and the doctors and nurses blessed with holy earnestness and solicitousness for human welfare.” She felt „she had become a little cog in an important community. I could do something to ease suffering and ease their last few moments in this world as they passed over into another world.”14

Familial resistance

In order to achieve their aims of becoming a nurse meant that it was necessary for many young women to break with tradition. As Thea Wolf in her youth attended to the Polish refugees, she heard her mother say everyday: “Prepare rather your dowry for your future household.” To escape from this kind of motherly admonition, Thea Wolf, in 1926 aged 19, secretly committed herself as “unpaid help”15 in the “Waisenhaus des Frauenvereins von 1883” (orphanage of the women’s association of 1883)” in Berlin. Thea Wolf commented on the reaction of her relatives to this with the words. “They were all persistently furious over my choice of career. They were of the opinion that I would have to give up a >normal life< that I would lead something like the life of a nun instead of going to a finishing school, to be taught how to be a good woman – and also learn to dance, in order then to get married. I wanted, however, something else, to go my way, help the poor and sick, as around me there was so much misery that I had experienced close at hand during the First World War.”16 During her time in the Berlin orphanage Thea Wolf came to know the loveless world in which the apathetic children lived. But neither this depressing experience nor the hostile stance of her family could dissuade her from her choice of career and she registered for nursing training. It was the rabbi who was later able to calm her parents down so that, in time, they became „really proud of their >nurse-daughter<„.

The aforementioned Gustav Feldmann had already said in 1901: „As a general rule applicants should be single.“17 It was assumed that the professional life of a nurse and marriage were not compatible, in most cases nurses on getting married left the nursing association. In order to keep the job attractive regardless of this, it was described as being excellent preparation for marriage.

Arrival as a nurse trainee in the Frankfurter Verein für Krankenpflegerinnen (Frankfurt Association for Nurses)

Charity of Jewish Nurses in Frankfurt am Main Report for 1913 to 1919, Frankfurt am Main 1920, page 48f

In 1927 Thea Wolf began her nurse training at Number 85, Bornheimer Landwehr, the

belonging to the

(Association for Jewish Nurses in Frankfurt am Main) .

Looking back she remembers her first day: I sat there with a sinking feeling for a few minutes but then

entered the room, greeted me in a friendly fashion and said: “I am the matron and I’ll take you to Nurse Dora. She is responsible for the nursing hostel and she’ll accompany you to your room.”

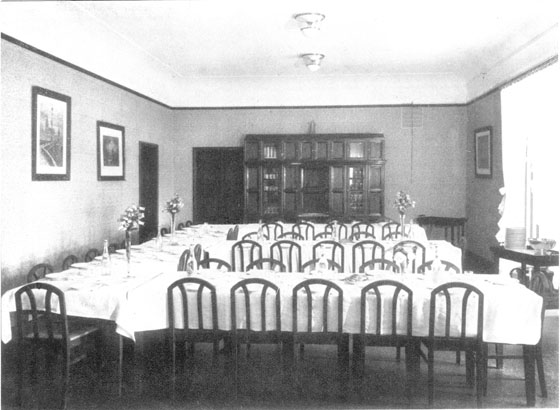

The room was on the third floor of the nursing hostel. I shared it with two other nursing trainees for the next two years, the length of time required to become a registered state nurse. We received our practical training in the (Jewish community hospital) in Number 36, Gagernstraße. […] A gong sounded at lunchtime and we ate on the ground floor in a spacious dining room. Frau Oberin Minna was introduced to us here for the first time. She had already retired and was no longer working. […] I was introduced to all the older nurses. They all wore gold brooches as a sign of more than twenty-five years of service. […] Nurse Dora introduced me to all the remaining nurses: >This is Nurse Thea, our newest addition.< I belonged therewith to a community, […] I went back to my room and […] wrote[…] to my parents and told them that everything was going wonderfully well, I had arrived safely and that I felt very comfortable.”18

Edgar Bönisch, 2009

(Translated by Yvonne Ford)